Gebruiker:ScienceDawns/Translate

Secularisme is het ideaal dat stelt dat er een scheiding dient te zijn tussen religieuze instituties en haar dienaren aan de ene kant en de staat en haar ambtenaren aan de andere kant. Het bereiken van deze soort samenleving wordt secularisering genoemd.

One manifestation of secularism is asserting the right to be free from religious rule and teachings, or, in a state declared to be neutral on matters of belief, from the imposition by government of religion or religious practices upon its people.[Notes 1] Another manifestation of secularism is the view that public activities and decisions, especially political ones, should be uninfluenced by religious beliefs or practices.[1][Notes 2]

Secularism draws its intellectual roots from Greek and Roman philosophers such as Epicurus and Marcus Aurelius; from verlichtingsdenkers such as John Locke, Denis Diderot, Voltaire, Baruch Spinoza, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Paine; and from more recent vrijdenkers and atheists such as Robert Ingersoll, Bertrand Russell, and Christopher Hitchens.

The purposes and arguments in support of secularism vary widely. In European Laïcisme, it has been argued that secularism is a movement toward modernisering, and away from traditional religious values (also known as secularisering). This type of secularism, on a social or philosophical level, has often occurred while maintaining an official staatskerk or other state support of religion. Differing political movements support secularism for varying reasons.[2]

Overview[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

The term "secularism" was first used by the British writer George Holyoake in 1851.[3] Although the term was new, the general notions of Vrijdenkerij on which it was based had existed throughout history.

Holyoake invented the term secularism to describe his views of promoting a social order separate from religion, without actively dismissing or criticizing religious belief. An agnostic himself, Holyoake argued that "Secularism is not an argument against Christianity, it is one independent of it. It does not question the pretensions of Christianity; it advances others. Secularism does not say there is no light or guidance elsewhere, but maintains that there is light and guidance in secular truth, whose conditions and sanctions exist independently, and act forever. Secular knowledge is manifestly that kind of knowledge which is founded in this life, which relates to the conduct of this life, conduces to the welfare of this life, and is capable of being tested by the experience of this life."[4]

Barry Kosmin of the Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture breaks modern secularism into two types: hard and soft secularism. According to Kosmin, "the hard secularist considers religious propositions to be epistemologically illegitimate, warranted by neither reason nor experience." However, in the view of soft secularism, "the attainment of absolute truth was impossible and therefore skepticism and tolerance should be the principle and overriding values in the discussion of science and religion."[5]

State secularism[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

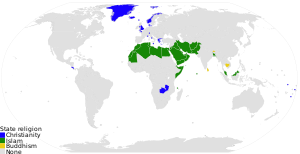

| 1 | ■ Islam | 1 | ■ Buddhism |

In political terms, secularism is a movement towards the separation of religion and government (often termed the scheiding van kerk en staat). This can refer to reducing ties between a government and a state religion, replacing laws based on scripture (such as Halakha, Heerschappijtheologie, and Sharia law) with civil laws, and eliminating discrimination on the basis of religion. This is said to add to democracy by protecting the rights of religious minorities.[6]

Other scholars, such as Jacques Berlinerblau of the Program for Jewish Civilization at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, have argued that the separation of church and state is but one possible strategy to be deployed by secular governments. What all secular governments, from the democratic to the authoritarian, share is a concern about the relationship between the church and the state. Each secular government may find its own unique policy prescriptions for dealing with that concern (separation being one of those possible policies; French models, in which the state carefully monitors and regulates the church, being another).[7]

Maharaja Ranjeet Singh of the Sikh empire of the first half of the 19th century successfully established a secular rule in the Punjab. This secular rule respected members of all races and religions and it allowed them to participate without discrimination in Ranjeet Singh's darbar and he had Sikh, Muslim and Hindu representatives heading the darbar.[8] Ranjit Singh also extensively funded education, religion, and arts of various different religions and languages.[9]

Secularism is most often associated with the Age of Enlightenment in Europe and it plays a major role in Western society. The principles, but not necessarily the practices, of separation of church and state in the United States and Laïcité in France draw heavily on secularism. Secular states also existed in the Islamic world during the Middle Ages (see Islam and secularism).[10]

Due in part to the belief in the separation of church and state, secularists tend to prefer that politicians make decisions for secular rather than religious reasons.[11] In this respect, policy decisions pertaining to topics like abortion, contraception, embryonic stem cell research, same-sex marriage, and sex education are prominently focused on.

Some Christian fundamentalists (notably in the United States) oppose secularism, often claiming that there is a "radical secularist" ideology being adopted in our current day and they see secularism as a threat to "Christian rights"[12] and national security.[13] The most significant forces of religious fundamentalism in the contemporary world are Christian fundamentalism and Islamic fundamentalism. At the same time, one significant stream of secularism has come from religious minorities who see governmental and political secularism as integral to the preservation of equal rights.[14]

Some of the well known states that are often considered "constitutionally secular" are the United States,[15] France,[16] Mexico[17] South Korea, and Turkey although none of these nations have identical forms of governance with respect to religion.

Secular society[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

In studies of religion, modern democracies are generally recognized as secular. This is due to the near-complete freedom of religion (beliefs on religion generally are not subject to legal or social sanctions), and the lack of authority of religious leaders over political decisions. Nevertheless, religious beliefs are widely considered by many people to be a relevant part of the political discourse in many of these countries (most notably, in the United States). This contrasts with other developed nations, such as United Kingdom, France, and China, where religious references are generally considered out-of-place in mainstream politics.

The aspirations of a secular society could characterize a society as one which:

- Refuses to commit itself as a whole to any supernatural views of the nature of the universe, or the role of mankind in it.

- Is not homogeneous, but is pluralistic.

- Is very tolerant of religious diversity. It widens the sphere of private decision-making.

- While every society must have some common aims, which implies there must be agreed upon methods of problem-solving, and a common framework of law; in a secular society these are as limited as possible.

- Problem solving is approached rationally, through examination of the facts. While the secular society does not set any overall aim, it helps its members realize their shared aims.

- Is a society without any official images. Nor is there a common ideal type of behavior with universal application.

Positive Ideals behind the secular society:

- Respect for individuals and the small groups of which they are a part.

- Equality of all people.

- Each person should be free to realize their particular excellence.

- Breaking down of the barriers of class and caste.[18]

Modern sociology has, since Max Weber, often been preoccupied with the problem of authority in secularized societies and with secularization as a sociological or historical process.[19] Twentieth-century scholars, whose work has contributed to the understanding of these matters, include Carl L. Becker, Karl Löwith, Hans Blumenberg, M. H. Abrams, Peter L. Berger, Paul Bénichou and D. L. Munby, among others.

Some societies become increasingly secular as the result of social processes, rather than through the actions of a dedicated secular movement; this process is known as secularization.

Secular ethics[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

George Holyoake's 1896 publication English Secularism describes secularism as follows:

Secularism is a code of duty pertaining to this life, founded on considerations purely human, and intended mainly for those who find theology indefinite or inadequate, unreliable or unbelievable. Its essential principles are three: (1) The improvement of this life by material means. (2) That science is the available Providence of man. (3) That it is good to do good. Whether there be other good or not, the good of the present life is good, and it is good to seek that good.[20]

Holyoake held that secularism and secular ethics should take no interest at all in religious questions (as they were irrelevant), and was thus to be distinguished from strong freethought and atheism. In this he disagreed with Charles Bradlaugh, and the disagreement split the secularist movement between those who argued that anti-religious movements and activism was not necessary or desirable and those who argued that it was.

Contemporary ethical debate in the West is often described as "secular." The work of well known moral philosophers such as Derek Parfit and Peter Singer, and even the whole field of contemporary bioethics, have been described as explicitly secular or non-religious.[21][22][23][24]

Secularism in late 20th century political philosophy[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

It can be seen by many of the organizations (NGO's) for secularism that they prefer to define secularism as the common ground for all Levensbeschouwing groups, religious or atheistic, to thrive in, in a society that honors freedom of speech and conscience. An example of that is the National Secular Society in the UK. This is a common understanding of what secularism stands for among many of its activists throughout the world. However, many scholars of Christianity and conservative politicians seem to interpret secularism more often than not, as an antithesis of religion and an attempt to push religion out of society and replace it with atheisme or a void of values; nihilisme. This dual aspect (as noted above in "Secular ethics") has created difficulties in political discourse on the subject. It seems that most political theorists in philosophy following the landmark work of John Rawl´s Theory of Justice in 1971 and its following book, Political Liberalism (1993),[25] would rather use the conjoined concept overlapping consensus rather than secularism. In the latter Rawls holds the idea of an overlapping consensus as one of three main ideas of political liberalism. He argues that the term secularism cannot apply;

But what is a secular argument? Some think of any argument that is reflective and critical, publicly intelligible and rational, as a secular argument; [...], Nevertheless, a central feature of political liberalism is that it views all such arguments the same way it views religious ones, and therefore these secular philosophical doctrines do not provide public reasons. Secular concepts and reasoning of this kind belong to first philosophy and moral doctrine, and fall outside the domain of the political.[25]

Still, Rawl´s theory is akin to Holyoake´s vision of a tolerant democracy that treats all life stance groups alike. Rawl´s idea it that it is in everybody´s own interest to endorse "a reasonable constitutional democracy" with "principles of toleration". His work has been highly influential on scholars in political philosophy and his term, overlapping consensus, seems to have for many parts replaced secularism among them. In textbooks on modern political philosophy, like Colin Farelly´s, An Introduction to Contemporary Political Theory,[26] and Will Kymlicka´s, Contemporary Political Philosophy,[27] the term secularism is not even indexed and in the former it can be seen only in one footnote. However, there is no shortage of discussion and coverage of the topic it involves. It is just called overlapping consensus, pluralism, multiculturalism or expressed in some other way. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory,[28] there is (amazingly) one chapter called "Political secularism", by Rajeev Bhargava. It covers secularism in a global context and starts with this sentence: "Secularism is a beleaguered doctrine."

Organizations[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

The Scottish Secular Society is active in Scotland and is currently focused on the role of religion in education. In 2013 it raised a petition at the Scottish Parliament to have the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 changed so that parents will have to make a positive choice to opt into godsdienstig onderwijs.

Another secularist organization is the Secular Coalition for America. The Secular Coalition for America lobbies and advocates for separation of church and state as well as the acceptance and inclusion of Secular Americans in American life and public policy. While Secular Coalition for America is linked to many secular humanistic organizations and many secular humanists support it, as with the Secular Society, some non-humanists support it.

Local organizations work to raise the profile of secularism in their communities and tend to include secularists, freethinkers, atheists, agnostics, and humanists under their organizational umbrella.

In Turkey, the most prominent and active secularist organization is Atatürk Thought Association (ADD), which is credited for organizing the Republic Protests – demonstrations in the four largest cities in Turkey in 2007, where over 2 million people, mostly women, defended their concern in and support of secularist principles introduced by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Leicester Secular Society founded in 1851 is the world's oldest secular society.

See also[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- Agnosticism

- Anticlericalism

- Atheism

- Antitheism

- Civil religion

- Clericalism

- Concordat

- Deism

- Freethought

- Humanism

- Ignosticism

- Islam and secularism

- Kemalism

- Kulturkampf

- Laïcité

- Multiculturalism

- Naturalism

- New Atheism

- Nontheism

- Pluralism

- Political Catholicism

- Political religion

- Postsecularism

- Pseudo-Secularism

- Rationalism

- Religious toleration

- Secular humanism

- Secular Review (journal)

- Secular state

- Secular Thought (journal)

- Secularism in Bangladesh

- Secularism in India

- Secularism in Iran

- Secularism in Turkey

- Secularism (South Asia)

- Secularity

- Secularization

- Separation of church and state

- Six Arrows of Kemal Atatürk

- State atheism

- Theocracy

Notes[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- ↑ See also Separation of church and state and Laïcité.

- ↑ See also Public reason.

Referenties[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- ↑ "Secularism & Secularity: Contemporary International Perspectives". Edited by Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar. Hartford, CT: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture (ISSSC), 2007.

- ↑ Feldman, Noah (2005). p. 25. "Together, early protosecularists (Jefferson and Madison) and proto-evangelicals (Backus, Leland, and others) made common cause in the fight for nonestablishment [of religion] - but for starkly different reasons."

- ↑ a b Holyoake, G.J. (1896). English Secularism: A Confession of Belief. Library of Alexandria, 47−48. ISBN 978-1-465-51332-8.

- ↑ {{Catholic Encyclopedia |title=Secularism |url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13676a.htm |prescript= |year=1912 |no-icon=1 | first=Charles |last=Dubray}}

- ↑ Kosmin, Barry A. "Hard and soft secularists and hard and soft secularism: An intellectual and research challenge.". Gearchiveerd van origineel op March 27, 2009. Geraadpleegd op 24 maart 2011.

- ↑ Feldman, Noah (2005). p. 14. "[Legal secularists] claim that separating religion from the public, governmental sphere is necessary to ensure the full inclusion of all citizens."

- ↑ Berlinerblau, Jacques, "How to be Secular," Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. xvi.

- ↑ K.S. Duggal, Ranjit Singh: A Secular Sikh Sovereign, Abhinav Publications (1989) ISBN 81-7017-244-6

- ↑ Sheikh, Majid, Destruction of schools as Leitner saw them. Dawn. Geraadpleegd op 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Ira M. Lapidus (October 1975). "The Separation of State and Religion in the Development of Early Islamic Society", International Journal of Middle East Studies 6 (4), p. 363-385.

- ↑ Feldman Noah (2005). pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Bob Lewis, 'Jerry's Kids' Urged to Challenge 'Radical Secularism'. The Christian Post (19 mei 2007). Gearchiveerd op 5 maart 2008.

- ↑ Rev Jerry Falwell, Jerry Falwell – Quotations – Seventh quotation (15 september 2001).

- ↑ Feldman, Noah (2005). p. 13.

- ↑ Mount, Steve, "The Constitution of the United States," Amendment 1 - Freedom of Religion, Press. Geraadpleegd op 22 april 2011.

- ↑ Preamble of the Constitution of India. Indiacode.nic.in. Geraadpleegd op 24 maart 2011.

- ↑ See article 3 of the 1917 Mexican constitution, and Article 24. See also Schmitt (1962) and Blancarte (2006).

- ↑ The Idea of a Secular Society, D. L. Munby, London, Oxford University Press, 1963, pp. 14–32.

- ↑ The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber, London, Routledge Classics, 2001, pp. 123-125.

- ↑ Holyoake, G.J. (1896). p. 37.

- ↑ Derek Parfit. Reasons and persons. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198246153.

- ↑ Brian Leiter, "Is "Secular Moral Theory" Really Relatively Young?, Leiter Reports: A Philosophy Blog, June 28, 2009.

- ↑ Richard Dawkins, "When Religion Steps on Science's Turf: The Alleged Separation Between the Two Is Not So Tidy", Free Inquiry vol. 18, no. 2.

- ↑ Solomon, D. (2005). Christian Bioethics, Secular Bioethics, and the Claim to Cultural Authority. Christian Bioethics 11 (3): 349–359. PMID 16423736. DOI: 10.1080/13803600500501571.

- ↑ a b Inc., Recorded Books, (1 januari 2011). Political Liberalism : Expanded Edition. Columbia University Press, pp. 457. ISBN 9780231527538.

- ↑ Patrick., Farrelly, Colin (1 januari 2004). Contemporary political theory : a reader. SAGE. ISBN 9780761949084.

- ↑ Will., Kymlicka,. Contemporary political philosophy : an introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198782742.

- ↑ 1953-, Dryzek, John S.,, Bonnie., Honig, (1 januari 2009). The Oxford handbook of political theory. Oxford University Press, pp. 636. ISBN 9780199270033.

Further reading[bewerken | brontekst bewerken]

- Secular ethics

- Berlinerblau, Jacques (2005) "The Secular Bible: Why Nonbelievers Must Take Religion Seriously" ISBN 0-521-61824-X

- Berlinerblau, Jacques (2012) "How to be Secular: A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom" ISBN 978-0-547-47334-5

- Boyer, Pascal (2002). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. ISBN 0-465-00696-5

- Cliteur, Paul (2010). The Secular Outlook: In Defense of Moral and Political Secularism. ISBN 978-1-4443-3521-7

- Dacey, Austin (2008). The Secular Conscience: Why belief belongs in public life. ISBN 978-1-59102-604-4

- Holyoake, G.J. (1898). The Origin and Nature of Secularism. London: Watts & Co., Reprint: ISBN 978-1-174-50035-0

- Jacoby, Susan (2004). Freethinkers: a history of American secularism. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7442-2

- Nash, David (1992). Secularism, Art and Freedom. London: Continuum International. ISBN 0-7185-1417-3 (paperback published by Continuum, 1994: ISBN 0-7185-2084-X)

- Royle, Edward (1974). Victorian Infidels: the origins of the British Secularist Movement, 1791–1866. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0557-4 Online version

- Royle, Edward (1980). Radicals, Secularists and Republicans: popular freethought in Britain, 1866–1915. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0783-6

- Asad, Talal (2003). Formations Of The Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4768-7

- Taylor, Charles (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02676-6

- Secular society

See also the references list in the article on secularization

- Berger, Peter L. (1967) The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. 1990 edition: ISBN 978-0-385-07305-9.

- Chadwick, Owen (1975). The Secularization of the European mind in the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39829-9

- Cox, Harvey (1965). The Secular City: Secularization and Urbanization in Theological Perspective. Edition from 1990: ISBN 978-0-02-031155-3

- Kosmin, Barry A. and Ariela Keysar (2007). Secularism and Secularity: Contemporary International Perspectives. Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture. ISBN 978-0-9794816-0-4; ISBN 0-9794816-0-0

- Martin, David (1978). A General Theory of Secularization. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18960-2

- Martin, David (2005). On Secularization: Towards a Revised General Theory. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5322-6

- McLeod, Hugh (2000). Secularisation in Western Europe, 1848–1914. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-59748-6

- Wilson, Bryan (1969). Religion in Secular Society. London: Penguin.

- King, Mike (2007). Secularism. The Hidden Origins of Disbelief. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co. ISBN 978-0-227-17245-2

- Secular state

- Adıvar, Halide Edip (1928). The Turkish Ordeal. The Century Club. ISBN 0-8305-0057-X

- Benson, Iain (2004). Considering Secularism in Farrows, Douglas(ed.). Recognizing Religion in a Secular Society McGill-Queens Press. ISBN 0-7735-2812-1

- Berlinerblau, Jacques (2012) "How to be Secular: A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom" ISBN 978-0-547-47334-5

- Blancarte, Roberto (2006). Religion, church, and state in contemporary Mexico. in Randall, Laura (ed.). Changing structure of Mexico: political, social, and economic prospects. [Columbia University Seminar]. 2nd. ed. M.E. Sharpe. Chapter 23, pp. 424–437. ISBN 978-0-7656-1405-6.

- Cinar, Alev (2006). Modernity, Islam, and Secularism in Turkey: Bodies, Places, and Time. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4411-X

- Cliteur, Paul (2010). The Secular Outlook: In Defense of Moral and Political Secularism. ISBN 978-1-4443-3521-7

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (1994). The New cold war?: religious nationalism confronts the secular state. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08651-1

- Schmitt, Karl M. (1962). Catholic adjustment to the secular state: the case of Mexico, 1867–1911. Catholic Historical Review, Vol.48 (2), July, pp. 182–204.

- Urban, Greg (2008). The circulation of secularism. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 21, (1–4), December. pp. 17–37.